Student for a Day at North Cascades National Park Headquarters

By guest blogger Elisabeth Keating

“The coolest part was when we went snorkeling in Ross Lake, looking for fish. Remember how cold it was?”

“We met a Spanish forestry Ph.D. student on the boat on Ross Lake. She’s here to study how we manage our forests because in her country, the forests have been logged so much they barely have any trees left. She told us she couldn’t believe how huge and unspoiled our forests are!”

“My favorite day was when we learned all about bears and the effect of climate change on bear habitat. I didn’t know the bears we have here were endangered, I thought it was all about the polar bears.”

“I’ll never forget watching the meteor showers when we were lying on the dock last night!”

“Remember how we held hands and ran the final few yards up to Desolation Peak? I couldn’t believe we made it!”

It’s a beautiful Saturday morning in the North Cascades at the North Cascades National Park Visitors Center in Newhalem, WA. As I walk the trails, I’m regaled with tales of scientific discovery and high adventure by 19 very enthusiastic and bright high school students. Freshly back from 19 days of hiking to Mount Baker’s glaciers and summiting Desolation Peak, riding out thunderstorms on Cascade Pass and exploring the underwater world of Ross Lake, the students are full of stories and it’s all I can do to keep up. Best of all it’s not over yet: still to come are 2 final days of camping, planning school projects that will extend the students’ learning to elementary school students, brainstorming and rehearsing presentations. Tomorrow, we’ll get an inside look at Diablo Powerhouse to learn about hydro electric power—a renewable energy source that must be balanced with protecting salmon habitat.

On today’s agenda: learning about national parks and putting in some time to plan what projects the students will bring home to their schools in the fall. Last summer, I spent an incredible day exploring the glaciers of Mount Baker with the 2009 students, and I can’t wait to learn about what this year’s crop of Cascades Climate Challenge students has been up to.

At ten AM, we meet the two Park Service rangers who will be our guides for the day: Will George from Oregon’s Lewis and Clark National Historic Park, and Autumn Carlsen, from North Cascades National Park.

Today will be spent at the Visitor Center. Though we won’t travel far we will get an in-depth look at how our national parks meet their stated mission: “…to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Our park ranger hosts begin the day by asking students to say hello to the person next to them, and push students to share their thoughts with a partner on why national parks exist.

The responses range from:

Andrea, of Astoria, OR: “We have national parks because people in other countries don’t.”

Shane, of Olalla, WA: “To keep nature preserved!”

Scott of Knappa, OR: “To preserve wilderness, wild life, and plants!”

Avery of Knappa: “Because we need wild places and places to get away from other people.”

Sierra of Pendleton, OR: “To preserve the last pristine wild.”

Colin of Vashon Island, WA: “Because people need wilderness more than they think they do.”

Ray Devlin of Vashon Island: “To teach about natural conservation.”

Ryan Devlin of Vashon Island: “So that we can be reminded that there were once larger wild places and to turn back to wild places.”

Stories vs. Statistics

After talking about what the parks mean to us, we head inside the Visitor Center to examine the vast scope of the North Cascades and for a lesson in the difference between stories and statistics when thinking about the true power of national parks.

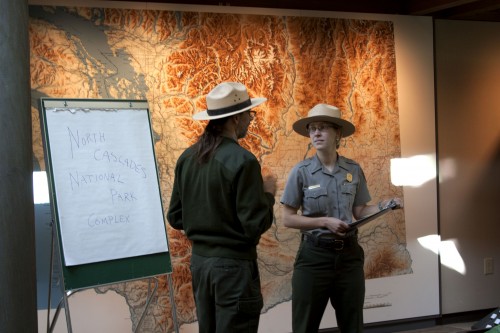

Our hosts use a wall-sized topographical map to introduce us to the vastness of the North Cascades National Park Complex. Three park units in this mountainous region are managed as one and include North Cascades National Park, Ross Lake, and Lake Chelan National Recreation Areas. These complementary protected lands are united by a contiguous overlay of Stephen Mather Wilderness. 93% of the park complex is congressionally designated wilderness.

The Wilderness Act of 1964 defined what a wilderness legally is, succinctly and poetically:

“A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

Students work with Ranger Autumn Carlsen to identify Desolation Peak, Ross Lake, Cascade Pass, Mount Baker and other places they’ve visited in the Climate Challenge course.

Students work with Ranger Autumn Carlsen to identify Desolation Peak, Ross Lake, Cascade Pass, Mount Baker and other places they’ve visited in the Climate Challenge course.

The rangers ask students to identify points on the map and throw out a lot of impressive numbers about the place we’re standing:

- North Cascades National Park was founded October 2,1968

- There are 3 dams on the Skagit River

- There are 312 glaciers in the Park

- 300 peaks in the park are over 7,000 feet high

- Within the Park, the elevation gain goes from sea level to a staggering 9000 feet

- Humans have been using Cascade Pass for over 8000 years. It was one of the major trading routes for Native Americans.

- There are 288 archaeological sites in the park.

- North Cascades National Park is home to:

- 1700 species of plants

- 200 migratory birds

- 75 species of mammal

- 28 species of fish

- 21 reptiles and amphibians

- There are 8 “life zones” in the park.

- The Picket Range, right outside our window, is entirely contained within North Cascades National Park. There are at least 21 peaks over 7,500 ft (2,300 m) high in the range.

Next, the rangers rip up the huge piece of paper they’ve been writing on. “In the end, none of these facts and figures really matter,” says Will. “What’s vitally more important is establishing a personal connection with the land and with a national park. By age 18, you have the power to help protect these incredible places. The power of your personal experience here the past 19 days will really help you to connect with the kids you’ll be teaching.”

To illustrate the power of personal storytelling in teaching about the Parks, we go into the auditorium to watch an excerpt from the Ken Burns documentary on the national parks, where Shelton Johnson, a park ranger, describes a life changing moment he had in Yellowstone as a young man:

One of the last jobs I had in Yellowstone was delivering the mail on snowmobile. And as I dropped down into Hadyn Valley, there were bison crossing over the road and it was so cold that the bison, as they breathed, their exhalation seemed to crystallize in the air around them. There were these sheets, these ropy strands, of crystals kind of flowing down from their breath. I remember stopping the snowmobile and turning it off, and listening. And I felt like this was the first day; this morning was the first time the sun had ever come up. I was all alone but I felt I was in the presence of everything around me. It was one of those moments when you get pulled outside of yourself into the environment around you. I forgot completely about the mail! All I was thinking of was that a single moment in a place as wild as Yellowstone can last forever.

After watching the clip, we discuss how National Parks provide a doorway into a transcendent experience—a sense of something that’s greater than yourself. The rangers say, “In the past 19 days, you’ve found a moment when you connected with this place. Think of a key moment that you can bring to the elementary school kids when you teach them.”

For Ranger Will, it was hike on an east side trail on Mount Rainier at sunset and meeting a bear. “I was scared, but I never felt so awake. National Parks can make you feel incredibly alive.”

We head outside onto the deck with a view of the magnificent Picket Range.

We head outside onto the deck with a view of the magnificent Picket Range.

Climate Challenge students recall moments of personal discovery in North Cascades National Park.

Climate Challenge students recall moments of personal discovery in North Cascades National Park.

A few stories emerge:

“I’ve had about eight moments of deja vu, where I’ve felt I had been here before somehow, even though I never have.”

“Watching the meteor showers from a dock on Ross Lake—we were all on the deck laughing and talking but there were also a few moments of complete silence. People find themselves and realize what’s important looking up at the stars.”

“Canoeing away after we had climbed Desolation Peak—I looked back and saw how far we had climbed and it felt amazing.”

It’s time for lunch. Our guides lead us down the River Loop Trail to where we’ll have lunch on the Skagit. The 1.8 mile loop starts from the northeast corner of the Visitor Center, leading through a variety of forest growth to a peaceful gravel bar with sweeping river views.

Heading down the River Loop Trail

Heading down the River Loop Trail

As we walk, the rangers explain the difference between the Forest Service, managed by the Department of Agriculture and the National Park Service, managed by the Department of the Interior. The mission statements are different: The Department of the Interior is dedicated to preservation of the natural resources and cultural heritage of the United States: The U.S. Department of the Interior protects and manages the Nation’s natural resources and cultural heritage; provides scientific and other information about those resources; and honors its trust responsibilities or special commitments to American Indians, Alaska Natives, and affiliated Island Communities.

The Department of Agriculture manages the natural resources of the United States: We provide leadership on food, agriculture, natural resources, and related issues based on sound public policy, the best available science, and efficient management.

Eating lunch and planning projects by the Skagit River

Eating lunch and planning projects by the Skagit River

As we eat our lunch, Will and the Astoria Oregon students discuss ways to approach the autumn teaching students will bring to the elementary school kids in their area. Will suggests they think about the local effects of climate change: for example how the watershed will be affected and how the increase in rainfall and decrease on snow pack will affect salmon—a big story in their neck of the woods. “Is your family involved in fishing? The best way to connect with kids is to think about the effect of climate change on their local environment.”

After lunch, we walk along the “To Know a Tree” Nature Trail which follows the river, wandering among large trees and lush growth. Along the way, we find plaques interpreting common trees and plants. Students discover a tree whose core was burned out by fire and the rangers explain that often trees continue growing, even after they’ve been burned, as everyone takes turn standing inside the living tree.

The Rock Shelter Trail takes us a 1,400 year old hunting camp sheltered by a large boulder along side Newhalem Creek. The shelter is an example of how national parks work to conserve and protect places of cultural significance.

Students look at the Rock Shelter, a 1,400 year old hunting camp where Native American butchered and preserved the meat of mountain goats and other animals. The National Park Service not only protects beautiful places—it also protects our cultural heritage, including battlefields and archaeological sites site as the Rock Shelter. (The platform students are standing on was built by Gerry Cook, captain of the Ross Lake Mule, a boat which has ferried the students on many adventures the past month.)

Next Steps

I talk with Anneka, one of the lead instructors. The course has changed this year from a single session course, to two 22-day sessions to that are offered to students throughout Washington and Oregon, as opposed to the whole country.

Students will go home and be expected to teach 6-12 year olds about climate change. But first, they must make a group presentation just three days from now at a YMCA in Mount Vernon.

They still need to polish their presentations and think about what they will teach in the fall.

After our trip to the Rock Shelter Will and Autumn lead the students in a discussion of the Climate Friendly Parks Program, a new project in the past 3 years. It encompasses 192 national parks and the North Cascades national park is a certified “climate friendly park.” What does that mean?

Will explains, “first it’s about how we spend energy: there’s no idling. We ask drivers to turn off engines after 10 seconds of waiting. We monitor our energy use, compost and recycle, and educate students about climate change and what they can do any school and at home.”

The parks will be offering Green Stickers soon, with an emblem of the local effects of climate change: for the North Cascades a pika for Lewis and Clark, a salmon.

“You pay $2 for a sticker and that offsets the carbon that you spent in the park.” The sticker will also have ideas on how to save energy.

Less Stuff, More Fun

“Taking care of the planet doesn’t have to be arduous,” Will says to the students. “It can be fun, and that’s important to convey to kids. You can do positive things that improve your life, like planting, bicycling, creating a community garden, buying locally at your farmer’s market; have a simpler and more enjoyable life. Even for those who don’t believe climate change is happening, simplicity plus sustainability = more fun.”

As the Center for a New American Dream says: “Less Stuff, More fun.”

Some parks are even experimenting with using biodiesel on buses.

“The important thing is, there’s lots of excitement and creativity going on. So when you teach, make sure you have fun and give the kids a chance to offer their ideas. Make it interactive. Think about songs, dances, creative and rich experiences.”

Passing the Torch

It’s late afternoon now, and time for students to brainstorm and split back into hometown groups to discuss how they’ll share what they’ve learned with elementary students. How will they inspire the younger kids back home with their newfound knowledge? A few ideas are floated:

Kindergartners painting recycling bins”

“A puppet show about recycling, featuring animal puppets of endangered species like bears, pikas, and salmon”

The Climate Change instructors as well as the rangers go from table to table to listen and offer suggestions while encouraging the students to drive the discussion.

The Vashon group isn’t sold on Will’s puppet idea. “I don’t know,” says Ray. “Puppets terrified me as a kid. We don’t want to scare the kids!”

The Wenatchee students are thinking about dams. “Maybe we could take them to the Bonneville Dam, and show them how the water level affect the fish. If you keep your energy use low, you’re helping out salmon.” The group debates whether the concept is too abstract. “What about going camping? And showing them the animals we’re trying to help?” “We can at least take them to the dam in April to watch the salmon run.”

The Astoria group is setting measurable themes, goals and objectives. Will suggests they consider the ages of students in developing their lesson. “With younger kids you can’t teach hard science, but you can teach broader conservation topics.” The group settles on the 3rd grade age group. They’ll have 2 visits to the school, 40 minutes each in length. Finally they will spend a day at Lewis and Clark National Historic Park. Since 40 percent of Oregon’s energy comes from coal, they will talk about air pollution. Their objective is clearly defined: “By the end of our talk, all the 3rd graders will be able to identify one way to conserve energy and reduce air pollution.” Their classes theme will be “How to Save and Conserve Energy.”

The Washougal and Wenatchee students consider setting up a composting project and planting trees.

The Walla Walla and Pendleton students think they’ll try a recycling contest between 5th grade classes.

Later that day, around the campfire, after several more rounds of discussions and presentation practicing, it’s time for today’s “Camp Philosopher” to read an inspiring quote for everyone to reflect on. Today the philosopher is Savannah. She reads a Chinese proverb, which reminds her both of what she has learned, and the way that the class will impart their knowledge to younger students:

“Tell me, and I’ll listen.

Show me, and I’ll understand.

Involve me, and I’ll learn.”

Tomorrow, we’ll get an inside look at Diablo Powerhouse to learn about hydro electric power—a renewable energy source that must be balanced with protecting salmon habitat.

Learn More

Department of Energy: Kids Saving Energy page

National Park Service brochure: Climate Change in National Parks

Climate Friendly Parks

Climate Friendly Parks: Do Your Part

North Cascades National Park Climate Friendly Parks Profile

All photos by Michael Silverman — many thanks!