Learning To Love Thorny Places

Hillary Schwirtlich is a graduate student in her third quarter of North Cascades Institute and Western Washington University’s M.Ed. program. She grew up in South Texas, moved to the Northwest for an AmeriCorps position right out of college and fell in love with the mountains. Hillary splits her time between the group rentals and ecological studies assistant positions at North Cascades Institute.

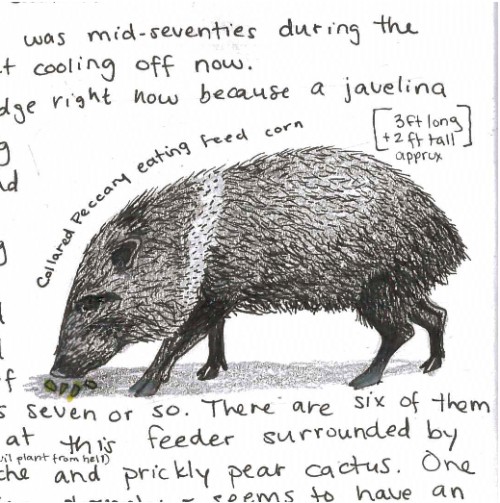

A collared peccary, locally known as a javelina, bluff-lunges at me from fifteen feet away, snapping its jaws together repeatedly. I’m cross-legged on the hard-packed dirt, eye-level with the salt-and-pepper animal, my entire body tense. I have a vivid memory of being hastily tucked in the crook of a mesquite tree by my dad as a child, and then watching him run from three or four angry javelinas. They can be aggressive if they feel they’re in danger.

After a couple of minutes, the javelina relaxes and returns to his group, which are rooting around for feed corn under a feeder on our 88-acre property in south-central Texas. It’s sunset in mid-December, and I’m in shorts and a t-shirt. I return to my natural history journal and make observations on the wildlife I’m seeing – at least five cottontail rabbits, a squirrel, and a bright red cardinal have made an appearance at the feeder this evening.

A drawing from the Natural History Journal that sparked this post. Drawing by the author

A drawing from the Natural History Journal that sparked this post. Drawing by the author

This natural history journal is opening my eyes to the biodiversity of my home for the first time in my life.

I never felt a connection to the ecosystem where I grew up. When I thought about nature near my home, I felt resentful. My family was blessed with the ability to travel, so I grew up vacationing to beautiful places—places like Lake Tahoe, Costa Rica, Puerto Vallarta and the Grand Canyon. When we returned home, my heart always fell a little as I saw the brown, flat, strip-mall-and-big-box-store riddled reality I lived in. Like most children, I still found places outside to create my tiny worlds, experiment and build structures, collect eggshells and poke ant hills, but my playground consisted of weedy, broken concrete slabs heaped on each other to keep Corpus Christi Bay from eroding the shoreline. Oil and gas refineries pumped pollutants on the far side of the bay while laughing gulls cackled over mud-colored waves. It was a far cry from the cloud forests of Costa Rica.

A storm rolls in over a cleared field on the 88-acre property. Photo by the author

A storm rolls in over a cleared field on the 88-acre property. Photo by the author

My dad bought the 88-acre property my freshman year of high school, planning to turn it into a pecan orchard. I used to bring my dog here, and we’d explored the trails on the property, which connected four or five deer feeders. She would chase armadillos and feral hogs out of the brush while I kept a lookout for cougars (which I never saw). The vegetation changed from mesquite brush and prickly-pear near the house to elm and oak near the Nueces River. When I left Texas, I remembered “the ranch” as somewhere brown, where everything has thorns and rattlesnakes are waiting under every woodpile and every pile of dry grass.

I still think of it that way, but something shifted when I visited over winter break. I brought my natural history journal—an assignment for the graduate program in which we record at least ten entries of observations of the natural world—and I wrote in it almost every day. Spending time making observations is slowly changing my perception of South Texas. Not only did I notice the abundance of shorebirds in the tidal mud flats near my family’s house on Padre Island, but I also started seeing the ranch a little differently. I realized how biodiverse and, considering the overwhelming ratio of private-to-public land and the general lack of respect for nature rampant in that part of the world, how resilient the ecosystem must be for me to see so much wildlife.

The author exploring Choke Canyon State Park in south-central Texas. Photo by Chris Clark

The author exploring Choke Canyon State Park in south-central Texas. Photo by Chris Clark

Nothing will ever take the place of the Northwest in my heart, but maybe South Texas isn’t all that bad.

Leading photo: Huisache (Acacia farnesiana), a fast growing shrub found in arid regions that sometimes seems to be made entirely of thorns. Photo by the author.

Thanks for this article, Hillary! I had a similar experience after returning to my home in Louisville, KY after the first quarters of the grad program. I’ve had it again after moving back here this year – I’m both surprised at how many parts of the natural world I recognize and amazed at how many I never learned growing up. Having relationships with more than one bioregion feels sort of like being able to speak two languages.

Love the illustration. It would be great if you had the time to create more.