Howling to be Heard: Wolf Evolution and Behavior

This is the second article in Mike’s “Howling to be Heard” series; you can read the first one on wolf folklore here.

Wolves have been a part of the American landscape for a much longer time period than humans have. Evidence shows that gray wolves appeared in North America around 15,000 years ago during a period of oversized mammals. The gray wolf’s much larger cousin, the dire wolf, was the primary predator until it went extinct about 8,000 years ago. It is believed by scientists that because dire wolves were much larger they could not keep up with the ungulates that had become much faster and adapted to run through forested areas after the retreat of the last glaciers at the end of the ice age. The smaller and quicker gray wolf, which hunted in packs, was much more suited to this newly forested environment. Following the extinction of the dire wolf, the gray wolf became the top predator in North America.

The gray wolf is the largest member of the Canid family and the third largest predator in the Northwest after the grizzly and black bears. The gray wolf’s closest relative, the coyote, has taken over much of the gray wolf’s former range due its near eradication during the early 20th century. It is believed that these two species separated on an evolutionary scale about 1.5 million years ago. In fact, all domestic dogs have evolved from gray wolves.

Other than primates, wolves have the most complex social structure amongst land mammals. The social structure of the wolf is centered around the pack, a group of 2-20 wolves that take on specific roles and functions within the community. Each pack has an alpha pair consisting of one male and one female, which is usually the only breeding pair within a pack. The rest of the pack members consist of the alpha pair’s offspring. Some pack members may eventually break away and set off on their own to either establish their own packs or join another. If a male leaves a pack or is kicked out by the alpha it will often become the alpha of another pack.

Aside from the alpha male and female there are several other roles and functions assigned to the different pack members. The alpha pair will rarely participate in a hunt, leaving that to the younger members of the community. The lowest ranking member of the family is the beta wolf, who is often picked on. The beta wolf performs the important role of diffusing tension between other pack members.

One of the most important roles in the wolf pack is that of the nanny. After the alpha female gives birth to a litter of 5-6 pups and concludes nursing she will assign a nanny to train and teach the pups. All wolves love pups and welcome new litters each spring. Pups are born blind and deaf in a natal den dug out by the alpha female. Pups grow and mature very quickly; they reach their full size by 14 months and learn to hunt during their first fall.

The highly complex social structure of the lives of wolves is rather unusual for large predators, who usually choose a solitary life. Mustelids (members of the weasel family), felines (cats), and bears all choose to hunt alone, only tolerating the opposite sex during mating season. This makes wolves a particularly interesting species that can contribute to a larger impact on the ecosystem as a whole.

The lifespan of a wolf varies in accordance to its proximity to humans. Wolf packs that live nearer to humans tend to undergo more human persecution and as a result have a shorter lifespan. Wolves in wilder, more open areas free from human development tend to live longer lives. The average lifespan for a wolf living in the contiguous United States is about 4 years, whereas a wolf living in Alaska has an average lifespan of 10 years. Wolves bred and brought up in captivity tend to live the longest, as they are free from human persecution and environmental hazards such as disease and starvation. Wolves in captivity have been known to live up to 16 years.

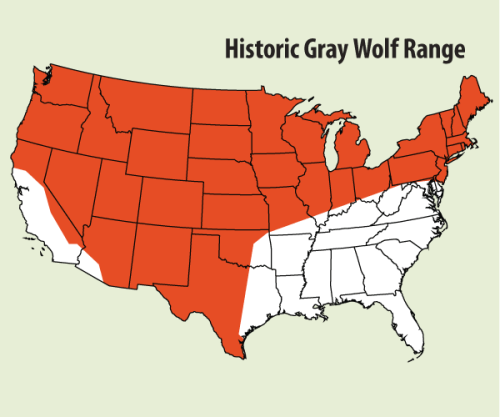

The historic range of the gray wolf extended from Alaska, into Canada, throughout most of the United States and into Mexico. The only unoccupied area was a small portion in the Southeast U.S. and along the Pacific Coast and central valley of California. As westward expansion in the United States teamed with deforestation, wolves experienced a dramatic loss of habitat and were hunted to near extinction. In the late 19th and early 20th century wolves were seen as pests and the U.S. government called for their eradication by placing a bounty on any wolf pelt. By 1960, the range of the gray wolf had shrunk from nearly the entire contiguous United States to the very Northern portion of Superior National Forest in Minnesota.

Right around the time of of the smallest gray wolf range in recorded history, Lake Superior, the worlds largest freshwater lake located around the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and the Canadian province of Ontario, froze over. With the freeze of Lake Superior moose were able to travel to a small island in the middle of the lake, which is now Isle Royal National Park. The wolves followed a few years later. During the first few years of moose being the only inhabitants of the island, biologists saw a dramatic impact on the island’s vegetation.

Plants were being eaten too rapidly and did not have enough time to recover. After the wolves made their way to the island, biologists noticed that the plant life started to recover. In 1958 a study was set in place to observe the impact that wolves have on an ecosystem. This study on Isle Royal still continues to this day and is the longest ongoing carnivore study in the world. Right when the wolf had nearly become extinct in the contiguous United States people began to see that wolves might not be the evil pests they were perceived to be, but instead have a profound impact on the ecosystem as a whole.

With the results generated by the Isle Royal study the playing field for wolves began to shift. Wolves had nearly been eliminated in the United States and then in 1973 congress passed the Endangered Species Act. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, who oversees the management of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), “The purpose of the ESA is to protect and recover imperiled species and the ecosystems upon which they depend.” In 1974, just months after congress had passed the ESA, the gray wolf was listed as endangered in the Lower 48 states and Mexico. The ESA prohibited people from hunting, persecuting, or disrupting habitat of the endangered gray wolf and gave it full protection.

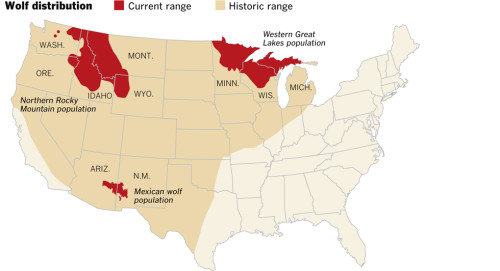

After the passing of the Endangered Species Act the range of the gray wolf slowly began to increase. By 1980, their range extended farther south into Minnesota, into Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and into Glacier National Park in Northern Montana. Wolf recovery was glacially slow for the first two decades after the passing of the Endangered Species Act, but in 1995 the world of wildlife took a dramatic turn of events.

Deep in the depths of the Rocky Mountains in two separate locations projects were about to begin to reintroduce the gray wolf back into the northern Rocky Mountain ecosystem. One reintroduction site was in Idaho’s Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness, and the other in Yellowstone National Park. Both programs were massively successful and the Yellowstone reintroduction project, which will be discussed more in depth in the blog’s next segment, became world-renowned.

After the reintroduction programs in the Northern Rockies and the protection under the Endangered Species Act the gray wolf population started to recover more rapidly. Today the wolf range is still only a fraction of what it was at the beginning of the 19th century, but it continues to grow. A range that in 1960 had shrunk in the lower 48 to the northernmost parts of Minnesota now has expanded to include Michigan, Wisconsin, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon.

There is new hope for the gray wolf and an optimistic projection of what the future range of the gray wolf looks like includes much of its former range. But wherever wolves go, controversy follows. With a viable wolf population they will continue to expand their range, but how far that expansion continues is ultimately up to us as people. We nearly exterminated the wolf only 50 years ago. We brought it back and could continue its expansion or nearly exterminate it again. The future of the gray wolf depends on our attitude toward the great predator. What do you think their future should be?

*Header image taken from Howling for Justice.