SPECIAL EVENT!: Evolution of the Genus Iris ~ Robert Michael Pyle Reading, Bellingham 5/10

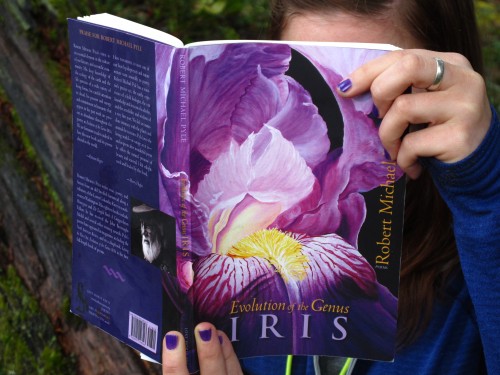

Evolution of the Genus Iris

A reading by Robert Michael Pyle

Saturday, May 10, 2014; 7 pm

Readings Gallery at Village Books, 1200 11th Street, Bellingham

Free!

“What a record we might have of the world’s hidden beauty if field scientists and poets routinely spent time in one another’s company.” — Alison Hawthorne Deming, from “Attending to the Beautiful Mess of the World” in The Way of Natural History

What better than a portable book of poems for a quick fix, one-way guarantee to reconnect with this hidden beauty which Deming conjures? A few stanzas, maybe just a handful of syllables, of sensory salvation for the time stressed, the pressed, those who have renounced staring dumbly at a screen or watching, heaven forbid, televised talking heads.

All Things Considered

Two river otters fished the Salmon,

diving and rising side by side, almost

down to the surf. Watching

their sleek and pointy loop-de-loop,

over and over and over,

I managed to miss

the evening news.

In his first full-length book of poetry, Evolution of the Genus Iris (Lost Horse Press, 2014), Robert Michael Pyle brings us the real news, live and uncensored from the natural world. A naturalist, lepidopterist, writer and field-class teacher at the North Cascades Institute, Pyle interprets the wild field with the eyes and notebook of both a scientist and a poet, as fellow writer Alison Hawthorne Deming wishfully imagines. The union is powerful. But Pyle does more than report from the web of life. He simultaneously offers solace from the verdant house of the holy by penning poetry that keeps us in the present, with feet grounded in the mud and moss. As he asks, also in the aforementioned book, The Way of Natural History, “Isn’t it enough that the pursuit of deep natural history is one of the surest paths toward an entirely earthly state of enlightenment?”

It is hard to ignore the genus Iris. (This is an heirloom bearded specimen from Alcatraz Island, part of another national park.)

It is hard to ignore the genus Iris. (This is an heirloom bearded specimen from Alcatraz Island, part of another national park.)

Pyle’s Evolution gives a resounding “yes”. Before exploring the book’s ecological innards, though, its cover alone is stunning enough: Purple Fire by artist Lexi Sundell, a painting of a bearded iris with brush strokes from lightest lavender to midnight plum. This tantalizing botany, in tandem with a blank first page of royal violet, is the paper portal into a majestic realm of words, wings and petals. Mimicking pollinators, let’s dive into the center.

The beautiful mess of the natural world: Can you spot the three small invertebrates snug in this lupine? From left to right: An unidentified tan spider, a bumblebee carrying huge sacs of tangerine-colored pollen, a crab spider. So much habitat in one inflorescence!

The beautiful mess of the natural world: Can you spot the three small invertebrates snug in this lupine? From left to right: An unidentified tan spider, a bumblebee carrying huge sacs of tangerine-colored pollen, a crab spider. So much habitat in one inflorescence!

I like/butterflies/quite a lot./But flies/(minus the butter)/abound,/and few/folks notice/except to/swat. So Pyle writes in “Dip-tych,” raising the banner for those less pretty, feces-loving insects even most naturalists seem to routinely kill without remorse or question. In another poem, “Releasing the Horseflies,” he becomes a screen-door naturalist: ….I can’t stand/frustration in any animal,/and a big fly battering a screen/is the very definition of frustration./And, oh! their stripéd silken eyes/are beautiful. Speaking up for the voiceless and the underdogs (or flies, in this case) is a specialty of both ecologists and poets. Pyle, embodying both, effortlessly lends his own integrity to this tradition.

The use of beautiful natural phenomena to elucidate hateful cultural shortcomings is another of Pyle’s talents as an author and a thinker. “Pink Pavements,” for example, uses the shattered blush blossoms of cherry trees to connect daily life across America to daily life in occupied Iraq. Or take “Blues,” which tracks the constancy of azure-winged butterflies and jays across twenty years while, during that same time, 58,022 names were added to the stone wall-list of fallen soldiers. Freedom may not be free, so some chant, but taking flight as bird, insect or flower petal seems the epitome of this cherished concept.

How the sidewalks flush and run/when cherries, crabs, and apples shed/their petal pelts. —from “Pink Pavements”

How the sidewalks flush and run/when cherries, crabs, and apples shed/their petal pelts. —from “Pink Pavements”

Pyle finds freedom in the quiet revolution of “The Librarians,” as well (The walnut will drop its leaves, and one of these nights/the spider will freeze. Books too will die,/they say. But don’t believe it.), and in the unencumbered play of children, as described in “The Girl With the Cockleburs in Her Hair:”

We were talking about how children don’t

get out any more. She showed me

her daughter on her cell phone:

big pout, and four big burs

caught up in her hair.

that girl, I said, is

going to be

okay.

(Also, semi spoiler-alert: Post-Evolution, it will be difficult to consider a baby bird or a tulip exclusive of each other again.)

Pyle’s 54 poems travel from Tajikistan to Yellowstone, yet some of the best honor local Pacific Northwest celebrities: banana slugs, salmonberries, Lookout Creek. It is exciting to read the names of various species and regional landscapes, like seeing a roster of old friends with their names illuminated on the marquee, our critterly comrades and natural wonders getting the recognition they deserve. There’s pipsissewa and oxalis and varied thrushes and more, many more — a huge sampling of local biodiversity bound in one celebratory book.

A Pacific Northwest gastropod celeb and famous decomposer, the banana slug.

A Pacific Northwest gastropod celeb and famous decomposer, the banana slug.

My personal favorite, though, was the collection’s last. “Notes From the Edge of the Known World” is made up of three meaty stanzas telling the story of the whole grand cycle, from birth and life to death and decomposition. This printed poem itself was enough — it was Every Thing after all, time and matter and space, the whole she-bang. But I’m a sucker for the Acknowledgements page, which followed, for who knows what connections and sweetnesses are to be found in the lists of helpful friends? Evolution‘s was no exception. I noticed that Pyle thanked Krist Novoselic, the bass player of a band from Aberdeen called Nirvana that rose to massive, worldwide popularity in September 1991. Perhaps you’ve heard of them? Nirvana was the band that put Washington state on my map when I was twelve years-old. The Vision! Not only did their lead singer teach me the word “empathy,” which I now use almost daily in writing and teaching about the natural world, but had I not been obsessed with running away to Seattle as soon as I got my driver’s license (which didn’t happen), I probably wouldn’t be here now, going to graduate school 19 years later.

So imagine this editor’s surprise and delight to discover that Pyle and Novoselic — who these days is busy with political activism, farming, writing and still, music — teamed up to present “Notes From the Edge of the Known World.” Pyle reads, Novoselic fingerpicks an acoustic guitar and youtube gives viewers easy access to a video interspersed with both the performers and ecological scenery (including a rough-skinned newt!). The writer and the musician are both active in organizing the Grays River Grange, in the Lower Columbia region of southwest Washington. The tune was recorded and mixed by Jack Endino, who also did Nirvana’s 1989 debut album, Bleach.

Good poetry the same as good ecology, and good music: It makes the fallible, all-too-conscious human feel not so alone in the world. Whether drawing out our kinship with a horsefly or with hanging blue cotton panties drying in the wind, Pyle shows, once again, that relationships are everywhere inescapable.

A monarch caterpillar munching on an Asclepias, or milkweed. This plant supplies monarchs with alkaloids that make them toxic to predators.

A monarch caterpillar munching on an Asclepias, or milkweed. This plant supplies monarchs with alkaloids that make them toxic to predators.

PLEASE JOIN NORTH CASCADES INSTITUTE AND VILLAGE BOOKS IN WELCOMING ROBERT MICHAEL PYLE:

The poet himself.

Evolution of the Genus Iris

A reading by Robert Michael Pyle

Saturday, May 10, 2014; 7 pm

Readings Gallery at Village Books, 1200 11th Street, Bellingham

Free!

Photo of Robert Michael Pyle by Benjamin Drummond. All other photos by the author.

Katherine Renz is a graduate student in North Cascades Institute and Western Washington University’s M.Ed. program. Though she rarely watches the Smells Like Teen Spirit video anymore, when she does she’s filled with regret that she failed to commandeer her high school’s cheerleading team.